“I am from the future but becoming the past.”—David Bartholomy

He would not answer to “Mr. Bartholomy.” He had his students call him “Bart.” He died Saturday.

No one influenced my writing more than this man. I am almost certain I would not have become a novelist if not for him. Meeting him forever changed me.

The above quote came from one of Bart’s countless writing exercises, from one of the three times I took his Wednesday night creative writing class at Brescia University. (He was also my teacher for ENG 101, ENG 102, Journalism 1 & 2, and Contemporary American Literature.) When he had us do his exercises, he always did them himself. Think about that: This was a teacher who gladly did his own assignments.

I can’t remember the writing prompt that produced the above quote (which I can confirm he came up with on the spot), but I can still remember it twenty years later because it’s so perfect—especially the first part. Yes, Bart was from the future. Anybody that had him as a teacher knows what I mean. He was so ahead of all of us in his progressive thinking, his intellectual forms of rebellion, his iconoclastic attitudes.

But “…becoming the past?” I remember even back then that this part bothered me. I thought, “Don’t you see? You’re younger than WE are.” But at the time he wrote it, he was around sixty, and obviously aging was on his mind. More on this later . . .

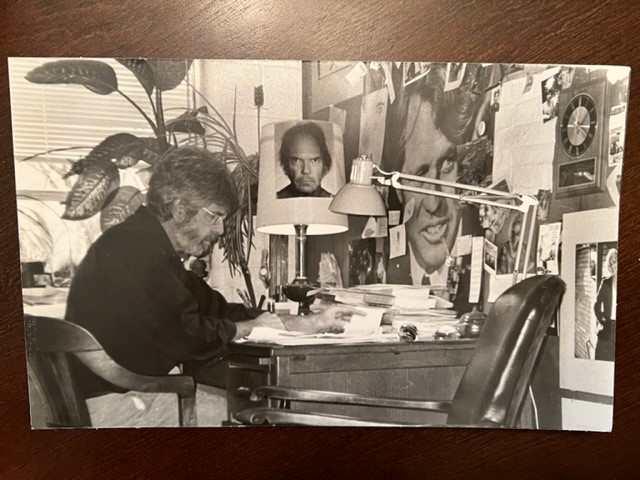

After our time in the classroom together ended, we remained friends through the years, and I would often visit him in the office you see in the photo. Stepping into that office was like entering the psychotic brain of a bohemian saint. The books, the records, the pictures of his dear family—just stepping into this room made you five percent cooler every time you visited.

If you’re one of my German or French readers, you’ve actually already met Bart. He was the basis for a supporting character named “Slim” in I Against Osborne. (America, apparently, is still not ready for Slim but might catch up someday in the future.)

If you’ve been one of my former students, you’ve heard me speak of Bart many times. When we first do fast-writes (a.k.a. free-writes) I always offer the same introduction:

“I learned fast-writes from the man who taught me how to write. We called him Bart. He was taller than God and had a beard before beards were cool. He was this charismatic, Bob Dylan-loving, bearded English teacher type, but so much more. He was intimidating at first but when you heard how softly he spoke and how he used green ink instead of red because it was less violent, you would soon realize he was a kind man. He was not quite a hippie, not quite a beatnik. I even detected some punk rock, but maybe I was projecting. Anyway, this guy went all out for his fast-writes. He would sometimes turn out all the lights, light some candles, and play some smooth jazz. I would think, ‘Man, are you trying to teach us or seduce us?’”

In terms of literature and writing, he most definitely seduced me. One Wednesday night, in helping me figure out which author to pick for my author report, we had a conversation that I now see helped lead me toward my later career:

“What kind of stuff do you read, Joey?”

“Uh . . . Mostly biographies on wrestlers.”

“I think we need to have you try something new. I know of an author that I think you’ll like.”

He loaned me his copy of Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut, who would go on to become my favorite writer. I have been a lover of literary fiction ever since. (He also turned me on to Charles Bukowski, Raymond Carver, and Tom Robbins. This led me to send my first novel to Robbins, and miraculously Robbins agreed to write me a blurb. I am told that his blurb helped get me some attention at the Frankfurt Book Fair, which eventually led to me finding my audience in Germany.)

Bart’s own textbook, Sometimes You Just Have to Stand Naked, is one that I have turned to repeatedly through the years for guidance in my writing.

One more pivotal conversation:

“These screenplays you keep turning in . . . Why are the lead characters always these dumb losers?”

“They’re supposed to be kind of like Adam Sandler movies.”

“They’re funny, but I can’t like a character like this. I can’t root for him.”

So then, when I was twenty, I wrote the screenplay for The Anomalies for his creative writing class. The lead characters were not loveable dumbasses. Instead, they were wildly individualistic, confident forces of nature. (A psycho-analyst might point out that Bart was actually helping me see myself in a different light.)

My all-time favorite moment as a writer was after he read the first thirty pages of The Anomalies screenplay, then came in the Broadcast office where I was nervously sitting on the couch, awaiting his response. (His approval meant the world to me, from the very first class on.)

He came in. I looked up all twenty feet. He smiled and said, “I love it.” I look back on that as the moment my writing career began.

Now, about that “. . . becoming the past” thing. Well . . . I know everything I’m saying here he would absolutely dismiss. That is always how he’d handle my praise, and I am relieved that I gave him all the praise I could while he was still healthy (“I’ve heard all your bullshit before,” he once told me.) If he were reading this, he would say, “I’m dead. Gone is forgotten.” He would say it’s official now: He has become the past.

But it’s just not so, Bart. You have become a PERMANENT part of so many people. Therefore, you are still part of the present which will carry into the future. For instance, take me. When I have a student point out that sometimes my classes feel more like therapy sessions than school—that’s Bart. When I try my best to view my students as my equals and tell them how much I learned from THEM—that’s Bart. I mean, this was a guy that would conclude each semester by asking his students what he could do to make the class better—and he had already been doing it over thirty years.

Finally, so much of his writing advice has remained “rules” for my own writing. He once said, “Never have your main character die in the end. That is lazy writing. Rather than have the character experience growth in the end, it’s like you’re saying, ‘I didn’t know what else to do with the bastard, so I just killed him.’”

But he also said that there is an exception to his rule, the instance where it becomes acceptable for a lead character to die. The lead character can die if his death (and his life) has AFFECTED change or growth in the OTHER characters.

Bart would also tell me not to treat the readers like they’re dumb.

“I think they’ll get it, Joe,” he would say, softly.